Gaia's Breath

On a beach at the edge of India, a migrant community dares to care for one another after society has failed them. Surviving drought, monsoon, and heat stroke, they go on, in search of a new home.

Mona Baby squeals, her thick, curly black locks bouncing as she races across the sand. She weaves through the crowd, her chubby legs stumbling every so often, straight into my arms. I press my salt-stained cheek against her soft, pale brown skin, close my eyes, and inhale.

I look around me, at the assembly of sun-soaked, brown-skinned humans on the hot sand. Some are huddled around fires’. The flames are nearly invisible in the bright white of the sky. They’ve begun cooking dinner, hoisting varying sized steel pots above the coals to steam rice, lentils, and harvested jungle greens.

Others are caring for each other: braiding jasmines into hair, rubbing aloe on sunburns, telling stories to pass the time. Beside us, the Indian Ocean extends into the horizon. It is a dull blue, spotted with dark concentrations of algae. Its warm waters gently nudge at the shore and leave behind soft patterns on the sand.

I press my fingers into Mona Baby’s thick locks. She is distracted by all the stimuli around her. Her big eyes are darting around the beach in search of the next place her plump toddler legs will take her.

I stare down at the contrast between my dark brown fingers and her pale, ruddy pink cheeks. When I was born, my Ammamma said it was as if I was plucked directly from our land. My skin was as dark and red as the ground. My hair was a deep brown, rather than black like hers and Mona’s. She said I was as restless as the changing climate. Running before I walked. Always up to something or seeking something new to do. Always outside, no matter the weather.

Twenty-five years ago, I was born into climate chaos, and thus I had no choice but to embrace the chaos itself. I am calm until I am enraged. I am in love with life until I am not. I am as much of the Earth as I am of the blistering sun that commands it.

Mona wriggles out of my grasp and dashes towards a gaggle of children who have gathered at the shore. She lets out a magnificent cackle as she half-hobbles, half-runs to them. They are all at least three years older and two feet taller than her, but that’s never stopped this baby. She’s fearless. I’m sure if Ammamma had met Mona, she would be reminded of me as a baby.

Despite my fearless beginnings as a child, today, I am full of fear. I am worried that it hasn’t rained in three weeks. Everyday gets hotter. Our supply of drinking water is running low. At best, we have one more week of sustenance and water until we won’t have enough for everyone.

Every time the weather edges above 35 degrees Celsius, we enter survival mode. I live in dread of this moment when our bodies stop being able to cope with the heat. They can’t cool down and our sweat can’t evaporate because of the humidity. Exposure to such extreme heat is fatal, especially for the old and sick among us. Even those of us who are healthy lose all our energy. Our heads ache, our minds fade, and our eyelids become heavy. We turn inward. Caring for each other becomes intensely effortful.

I shudder and stand up, full of worry. I look over at Radha and Sita. They are stirring large pots of rice in preparation for dinner and chatting quietly as they work. I stand up, brush sand off my salwar, and join them. The air feels thick and heavy today. Even more so above the fire. I wrap my arms around Radha’s shoulders. “Ayo, Kali-ji. Can’t you see how much I’m sweating already?” She shrugs her shoulders in an effort to get me off her.

I laugh and toss myself into the warm sand beside her, “Tell me, then, what are you two serious young ladies talking about?”

Sita sets down the stick she is using to stir the cooked rice, “I was remembering stories the elders used to tell us when we were young. They told us of a time when they could predict the growing seasons and monsoon season.”

“And now, none of us know such consistency. The droughts come and go when they wish. They stay as long as they want to and leave only to release brutal monsoons onto our heads,” Radha says bitterly. Ratha is at least five years my junior but she is as jaded as a seventy-year-old.

I stare out into the ocean, “Yes, I remember how my science teacher taught us about the ‘supercharging’ of the Indian Ocean and how it worsened wildfires in Australia and flooding in Africa. As the ocean temperatures have risen, and the vast ocean retains the heat, these disasters have become all we can count on.”

“Mm, how I long for a less volatile world, yet I have never known one,” Sita says, tracing circles in the sand. Sita has always been the more hopeful of the two.

The sisters are from what was Odisha, as it was known before the tumult of the past decades gradually dissolved our borders.

Radha and Sita were preteens when their family was displaced from their farm on the coast of Western Odisha. The government had built a dam in an effort to prevent flooding in the region and facilitate irrigation. But many villagers were displaced, and none were given compensation. Their family bought a small amount of land and prayed that the irrigation and monsoons would save them from predicted drought.

However, the drought arrived with such ferocity that their crops never grew. Small farmers like Radha and Sita’s family were left desolate. Their parents had borrowed money from moneylenders for fertilizers and pesticides to increase their odds of getting a good crop. Their parents both committed suicide, overwhelmed by debt and infertile soil.

Stories like this are tragically common in the Community. Unsustainable farming practices and government’s failure to enact major reform led to thousands of suicides, mass starvation, and devastated the economy, as the climate crisis intensified. Ultimately, this negligence is what led to the series of coup attempts and the final successful overthrow of the government a few years ago.

I shiver at the remembrance of such violent times. So many lives lost, and for what? For denial of a perilous crisis that scientists had warned us of for nearly a century? For utter lack of adequately protecting and serving the people of the world’s “greatest” democracy? The sad truth is it took a climate catastrophe for us to arrive at something remotely close to goodness. It took great suffering and death for us to realize one another and to hold that connection as sacred above all.

Twenty-five years ago, I was born into climate chaos, and thus I had no choice but to embrace the chaos itself. I am calm until I am enraged. I am in love with life until I am not. I am as much of the Earth as I am of the blistering sun that commands it.

People are starting to gather around a small nearby fire. Various sized pots and pans surround it, primarily filled with dahl and steamed greens. Radha, Sita, and I stand. The sisters set the rice down in the middle of the circle.

My gaze is drawn to the outside of the circle where the jewel of this meal sits: slices of beautiful guavas and juicy pomegranates. Both of these drought resistant fruits bring us joy amidst the bleakest of circumstances.

I sit down next to Mona’s mothers, Ramya and Parvathi. Sailash and Chinnu, father and son from coastal Bangladesh, are sitting with them. Parvathi is grimacing and bending forward. Sailash is soothing her, rubbing her back gently, as Ramya coaxes something inedible out of Mona Baby’s stubbornly clenched jaw. The lack of consistent sustenance combined with the mostly lentil meals does not sit well in Parvathi’s pregnant belly, and the frequent hunger only increases Mona’s curiosity about random items found on the ground.

I reach into my pocket and pull out some wild ginger I found this morning in the forest. I touch Parvathi’s thin shoulder, and hand her the ginger. She smiles gratefully through her grimace. The root will help soothe her already angry stomach after our meal. Sailash takes a small, worn knife out of a satchel fastened to his dhoti and begins to peel the ginger.

“We ventured out past the jungle today, Kali-ji,” Sailash says.

“Mmm?” I reply, watching the root’s thin peel fall and blend into the sand.

He nods, “There are several rocky hills after the forest ends. We climbed over them with some difficulty. And when we arrived at the highest point, we saw something in the distance. We can’t be certain because of the haze but -- it looked like an FVC… except smaller… a Future Vision Village.”

I cringe inadvertently. In recent years, global governments constructed what they dubbed “Future Vision Cities”, or FVC, that welcomed the elite into an urban utopia and pushed the poor and working class into surrounding slums, much like the Lost City of Dubai over a century ago. The government of India built hundreds of these cities in order to compete with China in its NextGen urban plan. They engineered complete techno-ecosystems in these places, which aimed to meet every citizen’s need with the ultimate intention of establishing order over them. In this way, India and much of the Global South became a living lab for the Global North, whose governments were completely losing control over their people, to observe.

In North America, South America, and Europe, riots and attempted coups were a monthly occurrence—they would come later to the Indian subcontinent to ensure the government’s final fall. The near century of fascist, right wing leaders that had run human society into the ground had resulted in a near complete loss of trust in the government. However, at the same time, the climate crisis was intensifying, and life was becoming harder. So, when these tech hubs promised an easier life to the wealthy classes, they jumped at the opportunity.

Government leaders in the Global South celebrated themselves as pioneers. The reality was the Global North was so concerned about the drawbacks of completely-automated cities that they funded their inception in the Global South to see what would happen. Ultimately, the climate catastrophe, their complete climate inaction, and democratic breakdown got to them before they were able to make a decision on whether to build such cities in their own formerly wealthy and democratic countries.

Sailash senses my trepidation, “I know how it sounds. But we were curious, so we continued through the ghat and past the mountains. As we approached, we were overcome by a feeling we couldn’t describe. There was something… magical about this place. We saw small temples and groups of people meditating together. We saw eco-homes and intra-village transport systems for crops. We did not let them see us. We hid behind the boulders at the base of the mountain. We wanted to share this with you first and ask what you think of heading there next.”

For a second, I forget to take a breath. Sailash and Parvathi look at me expectedly. Parvathi giggles and tousles my hair.

“Kali-ji is rarely surprised. But when she is, look how big her eyes get and how her jaw hangs open.”

I close my mouth and roll my eyes at Parvathi.

There is so much hope in Sailash’s words. A community that has built a settlement and is cultivating crops? I haven’t seen such a thing since we left what remains of Hyderabad up north several months ago. And even then, there were no crops—just shanty towns and a handful of vendors with withered produce and overpriced bags of imported rice and lentils.

“You were there, Ramya?” I ask, at a loss for words.

“Auh, ji,” she says in affirmation. “I saw it too. There was a serenity to the space. An aliveness that I haven’t seen in years. Just imagine if they were like us. Imagine if they shared our dreams for community and relationship with the land. Imagine if we had a place to call home.”

“Well, I suppose now we know where we could go next. We’ll send a few scouts out tomorrow morning. Of course, this will mean getting everyone through the ghat safely, but it’s worth it. This community you found has so much promise,” I say, already planning the journey in my head.

Sailash, Ramya, and Parvathi nod, full of thoughts and hope.

In contrast, Chinnu and Mona squirm, barely able to wait another minute until food is served. Chinnu’s big eyes and skinny neck look comically bug-like as he careens over his guardians’ heads to gaze at the food.

“Chinnu,” I ask, “What mischief did you get up to today?”

Chinnu smirks, content with his reputation as the Community’s rascal, “Nothing, Kali-ji. I just played in the jungle with the other children.”

“More like he went and fed Mona Baby the jungle,” said Ramya, still struggling to clean something resembling dirty rocks from Mona’s mouth.

“Chinnu anna said I can be like Lord Krishna if I eat dirt he brought from the jungle!” Mona sings, accidentally biting her mothers hand as she talks.

“Chi! Mona! Stop talking!” Her mother scolds her.

“Can you see the universe in my mouth, Mummy?” she asks gleefully, referencing the Hindu myths I tell her before bedtime as she shoves her mouth closer to her wincing mothers face.

Chinnu laughs, finding humor in Ramya’s struggle with her stubborn baby. Sailash swats his teenage son lightly and lovingly on the shoulder.

Chinnu and Sailash had been separated from their family in one of the early waves of migration, a decade ago. Just after Chinnu was born, his mother traveled north with his two sisters and her mother and father hearing from relatives and the daily news that there was ample dry land for farming and possibility of a more peaceful life. The plan was for Sailash and Chinnu to go to Sailash’s parents home in Eastern India and make enough money to bring all four of them to where the rest of them had settled.

But the climate had different plans. The season bore no crops on Sailash’s family farm and there was no money for travel that year, nor during years to come. The family was stuck in limbo, and when Sailash’s parents passed five years ago, managing the farm and paying the rent was untenable. The father and son had to move on. Sailash had heard of groups like ours gathering on the coast and decided to bring his son there, for fear they wouldn’t survive the journey up north to his wife and daughters without money to buy their way there. It took them several years and far too many run-ins with ill-intentioned or dysfunctional groups before they found us.

Stories like this were very common. In the last decade, when the tides began to rise and the climate became increasingly volatile, many Bangladeshis and Maldivians fled up north to China or Russia or further into India, or flew to Canada or the United States, seeking refuge from their now underwater homelands. No matter where they went, they were met with hostility around sharing land and resources.

Now all of us–Indians, Sri Lankans, and the remaining Bangladeshis–have been forced from our homes. And just like the first refugees, we were given no support from the Indian government. Instead, they evicted those of us like Sailash who couldn’t pay rent due to the impacts of climate change on our farms and livelihoods. Even those of us who managed to make rent were not protected from the natural disasters and hardships that plagued our every day.

There is a lot of sorrow in losing our homes. But there’s freedom, too. From oppressive governments and systems. Now we answer only to one another. We live under no assumptions of ownership. Instead, we create home in one another. We care for one another. We move across the land when the needs of our Community call us to seek sustenance or safety.

Across the circle from me Ram, a priest from the hills of Andhra Pradesh, stands,

Beloved,

May you be fed, watered, sheltered, and loved by the Divine Mother.

May you find peace in solitude within your Divine Self.

May you be held by this Divine Community.

May you one day pass on with ease to join the Divine Light.

We share a single, resounding aum and Ram hits a pocket-sized gong three times.

There is a lot of sorrow in losing our homes. But there’s freedom, too. From oppressive governments and systems. Now we answer only to one another.

Ram was one of the first members of this Community. In fact, he started it along with my Ammamma six years ago. Back when the world order was crumbling, a small group of people dared to imagine this Community. They founded it on the belief that collective care is critical to our survival. They also founded it on something more ethereal: the belief that an intentional community that values nature and practices meditation can access the cooling, healing power of the sacred Gaia, thus opening up the possibility for the dying human race to have a future. During the beginning years of Gaia, I was still living safely in the United States. The group was much smaller and suffered from the dysfunction that many other groups of nomadic climate migrants suffer from. But by the time I was forced to flee my home and find my way to my living family members three years ago, the group had clear community norms and practices, and a vision for the future.

Ram begins to speak. His voice is resounding despite the open expanse of the beach, “This evening, we come together for our final meal of the day. We nourish not only our own bodies, but that of the Divine Mother, Mother Earth. We nourish the Mother so that we call upon her ancient, earthly power in times of great need, times when this fast-warming world becomes inhospitable for our mortal bodies.

“We thank the Mother for this humble meal and recall our deep daily commitment to mending the fraught relationship between humans and nature. When we elders started this Community, we had lived only in South Asia. We witnessed the vast inequities revealed by climate change. We saw the way the climate crisis exacerbated the broad injustices that had been growing for decades. Then we saw human civilization collapse, and the horrifying chaos that followed. But we knew the solution to this chaos was tied to community and meditation.”

Chinnu squirms beside me, silently begging for the meal to begin.

“I thank you all for sharing this meal with me, and for spending each day seeking right relationship with this land.”

Chinnu exhales dramatically. We begin passing around the food, scooping it onto banana leaves. The group dissolves into chatter. The children flit about the circle. Adoring adults feed them mouthfuls of rice and dahl before they dash off to the next group.

I look around the circle at their faces. They are lit up by the fire’s glow and the setting sun’s final light.

I turn to face the sun. It lingers on the horizon, shooting a gradient of purple, blue, and pink across the sky. In its majestic wake, I simultaneously feel my very human insignificance and the great miracle of the chaos of the universe that has led to my existence.

I close my eyes and picture our journey ahead. For the six years that Gaia has existed, we have always been nomadic. Jumping from one safe haven to the other, settling on beaches, in fields, and bunkering up with other communities. We hadn’t yet come upon a functioning city to join, even though we had a vision for the settlement we wanted to create–structurally and culturally.

If the scouts return tomorrow with a positive assessment of the plan, this seems like the right next step for Gaia. It is what Ammamma would have wanted. She was anxious for us to settle and build. The journey will undoubtedly take time, given the number of elders and children in our Community. But our stores will last and maybe, just maybe, at the end of the journey, our hopes for fertile land to plant seeds in and build a stable home around will materialize.

I let my brain wander to my imaginings of the strong community we can build with our commitment to collective care, solitude, togetherness, and shared food. I imagine what our brains can design and implement together: eco-homes, irrigation systems, sustainable farming methods. We will be in the right relationship with the creatures around us and the land and water that gives us life. I see so much potential for a good life in spite of the planet’s demise.

Tomorrow, we will leave this beach and walk together towards hope for the future. This is something we have not had in months, not since the night Ammamma died.

Back then, the heat had topped 40 degrees Celsius for nearly two weeks. We had been out of water for 24 hours. The only food we had in our stores was shriveled lentils and a handful of rice. Few of us had interest in continuing to live. I spent most of my time leaning against a towering banyan with Ammama’s head on my lap. I stroked the thin white wisps of her hair as she hummed. I whispered stories to her, valiant myths of Krishna and Arjun and playful fables of the animal kingdom.

The banyan tree I was leaning on was known for the bustling life it hosted, but in those weeks, it was perfectly still. Its branches did not sway. Few creatures darted about its limbs. Its leaves seemed to sag with the weight of the sun’s rays. Yet it provided shade for all of us through to my Ammamma’s dying breath.

After she died, when we gathered to commemorate her life, something unexplainable happened. The heat lifted. Her lifeless body lay in the middle of our circle and we watched her translucent spirit rise and take the form of a cool breeze.

I recall the overwhelming awe. I remember feeling like something was watching over us—maybe even caring for us. We sat together under the banyan tree and noticed the ways our bodies responded to the newfound breeze. Soon after, when we had buried her body and rested together, we came upon a small reservoir of water. Here, we drank, bathed, and rested, relieved of the impossible burden that heat and imminent death brings.

Our stores from this reservoir have lasted us until now. They were her dying gift to us–a few more months of sustenance. Now it is time we rise together and build the Community she imagined. Not one of scarcity and fear, but one of possibility and resourcefulness.

I reach over to Baby Mona who is wolfing down her rice and lentils, spreading more across her cheeks than in her mouth, and gently tussle her thick, wild curls, smiling quietly at this possibility for her future, and for Gaia’s.

Denali Sai Nalamalapu is a queer, South Indian American writer, artist, and climate activist originally from Maine and currently based out of Washington, D.C. You can find more of Denali's work on her website (denalisai.com) and follow her on Twitter (@Denali_Sai).

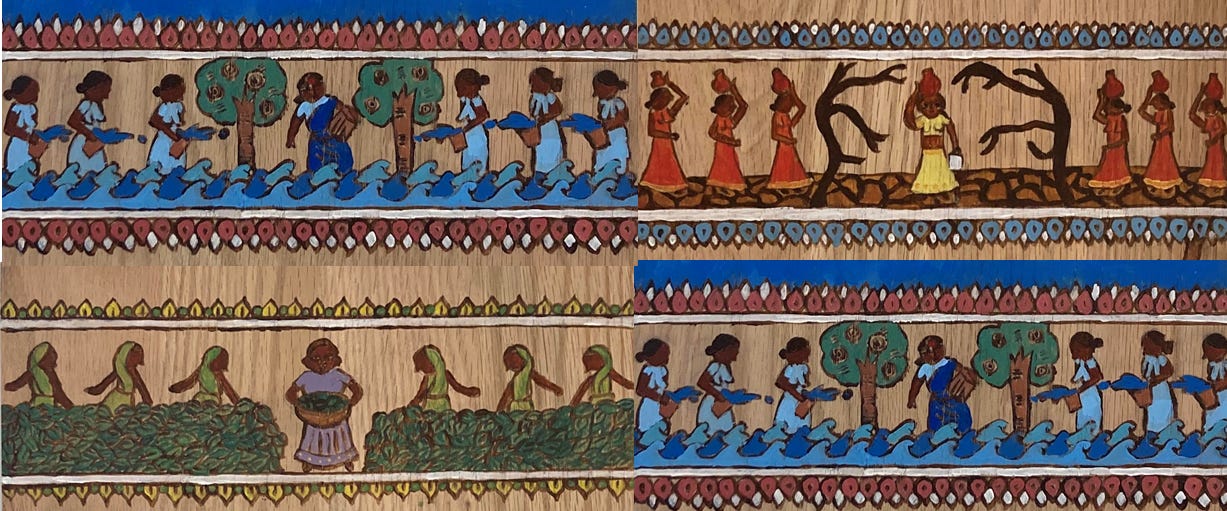

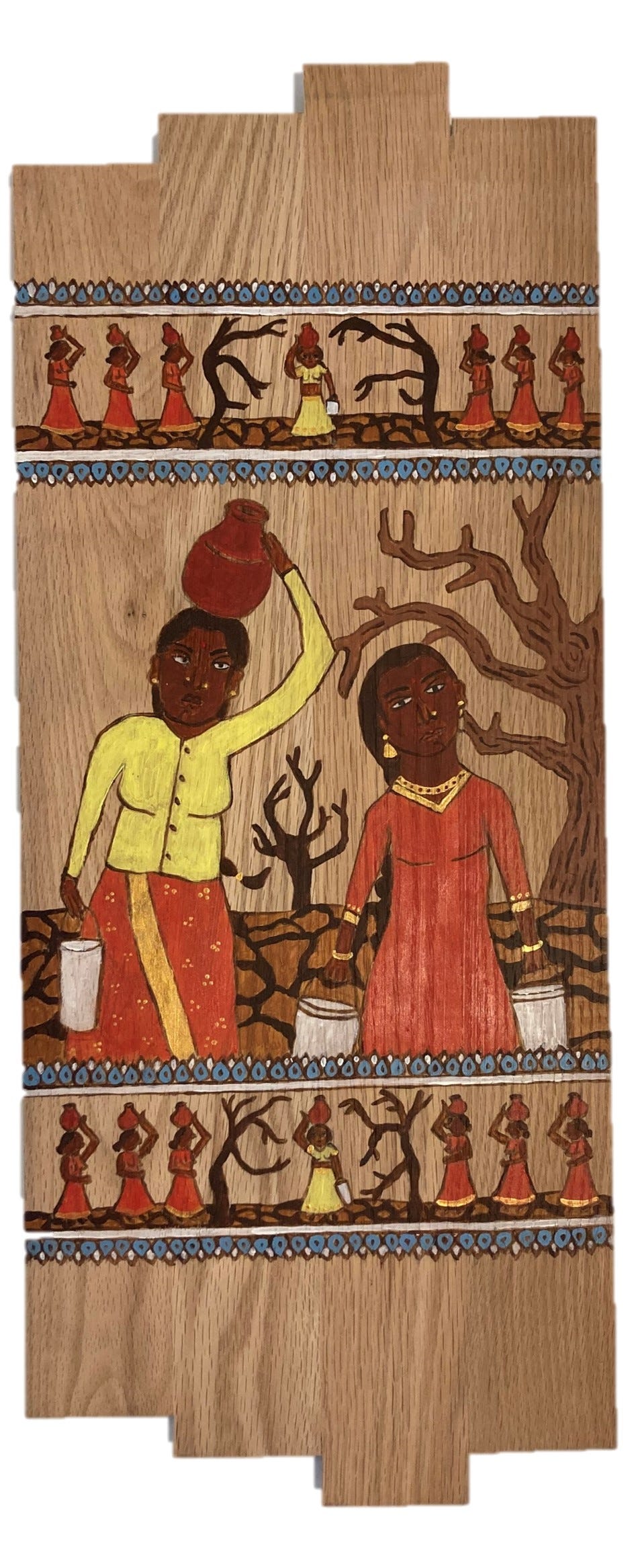

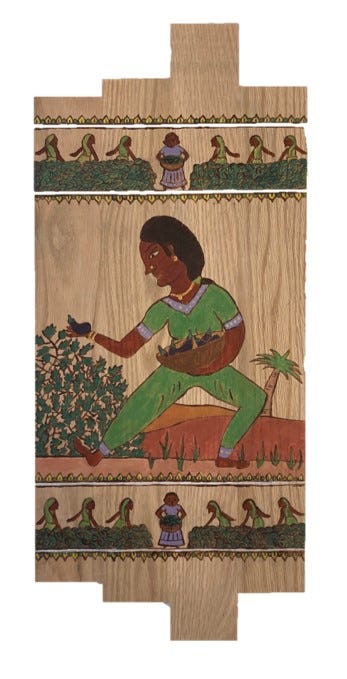

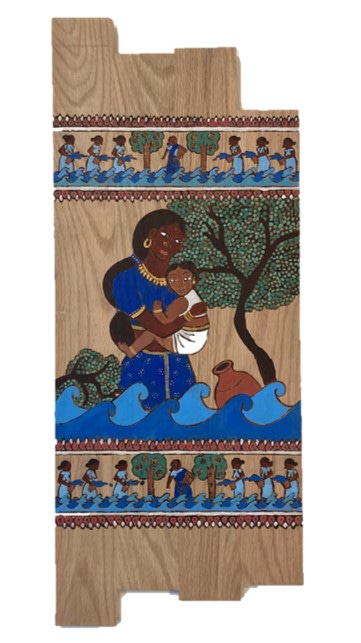

Denali also created the artwork that accompanies this story. She was commissioned to create this painting series by The Center for Culture Power as part of their Climate Woke project. Each image depicts dark-skinned South Indian women doing care work amidst the climate crisis. They are painted on recycled oak floor boards, using acrylic paint.